Choosing and Using a Wood Cookstove

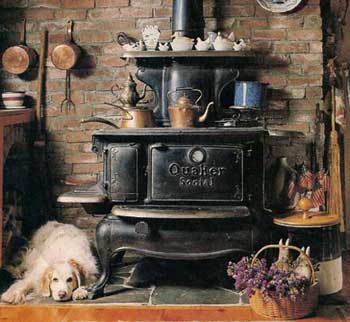

There are several reasons to consider owning a wood cookstove. In an emergency, they can provide a source of heat and a way to cook. You are not dependent on outside utilities, just your own ability to obtain wood or coal. Even more rewarding is the feeling you can get from them. I can look at my stove and wonder who has cooked on it, whose child bathed in front of it, and who used it to warm up chilly hands and faces on a cold day. I can also think of the memories we have made around it—the Thanksgiving turkeys and fragrant cakes and pies that have come out of it. I appreciate it for making me more self-reliant, but I love it for letting us share in its history and continue the warmth of its traditions.

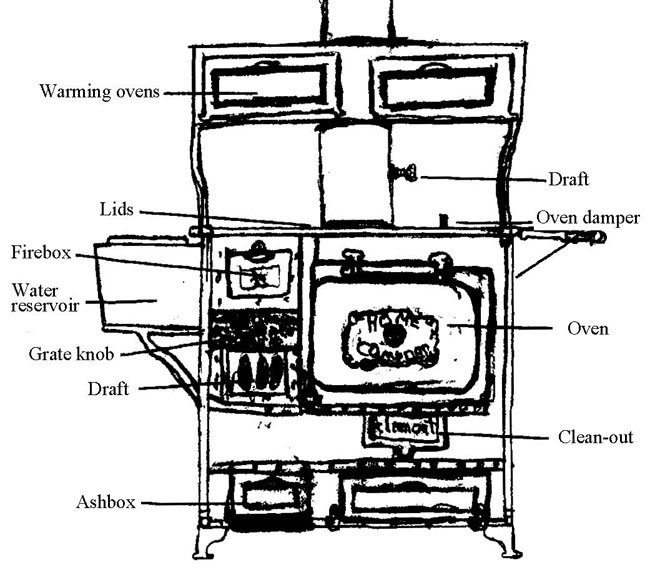

If you don’t already own one of these beauties but would like to, there are some things to look for. First, check the grates in the firebox on the left hand side of the stove. This is what the fire sits on as it burns. If they are gone or pieces of them are missing, make sure you can find a replacement for them before you buy the stove. This is the heart of the stove, because without the grates there is nowhere to build the fire. The grates should also turn to empty the ashes into the ashbox. There should be a square knob sticking out the front of the stove below the firebox. Take the grate handle, which is a handle with a square hole in it, place it on the knob and turn. Watch the grates move and make sure they don’t bind.

If you don’t already own one of these beauties but would like to, there are some things to look for. First, check the grates in the firebox on the left hand side of the stove. This is what the fire sits on as it burns. If they are gone or pieces of them are missing, make sure you can find a replacement for them before you buy the stove. This is the heart of the stove, because without the grates there is nowhere to build the fire. The grates should also turn to empty the ashes into the ashbox. There should be a square knob sticking out the front of the stove below the firebox. Take the grate handle, which is a handle with a square hole in it, place it on the knob and turn. Watch the grates move and make sure they don’t bind.

Second, look at the cooktop to make sure it is fairly level and not warped. Also check to see that the support pieces and the lids (those round things on top) fit together well. Any large gaps will smoke.

Third, look inside the oven for holes in the wall. If it is rusted through anywhere you’ll have a great smokehouse, but it won’t do much for your cakes and pies.

Many cookstoves also come with warming ovens or shelves and/or water resevoirs, which are great but not essential to their operation.

As with any wood burning stove, proper installation is vital to your safety, happiness, and the success of your new cooking experience. You should check local building codes to insure that you are in compliance in order to avoid an unplanned housewarming.

Wood cookstoves work on a very simple premise. You make a fire in the firebox and the heat travels beneath the cooktop on its way up the chimney. As it does so the cooktop gets hot. If you want to use the oven, you close the damper which sends the heat beneath the cooktop and around the oven before going up the chimney. This heats the oven. The only big adjustment comes when you realize you can’t set the burner on high or medium and you can’t set the oven for 350, wait 5 minutes and bake. With a regular stove, you start preparing the food, then turn on the heat. With a cookstove, you start the fire, then prepare the food.

All cookstoves have the firebox with a draft below it and an ashbox below that to catch the ashes. There is also a lever, either on the top or the right side, which controls the oven damper. There may also be a draft control in the stovepipe. When starting the fire, make sure eveything is in the open mode. Double check so you don’t end up with a kitchen full of smoke. Turn the grates to empty the old ashes and pieces of wood into the ashbox. Empty the ashes in the ashbox into something fireproof and place it on something non-combustible. I melted my floor by putting what I thought were cold ashes into a plastic bucket on a vinyl floor.

Most cookstoves will burn wood or coal, but using coal will cut the usable life of your grates down substantially. If you can get replacement grates easily, go ahead and use coal if you want to. But if you have to scavenge parts off another stove to replace your grates you’d be better off just using wood.

Start the fire using good, dry kindling. Don’t start with pieces that are too big, unless you enjoy stirring sooty pieces of wood around. Take the lids off over the firebox to lay your fire. Light the kindling (I use newspapers underneath) and put the lids back on before your ceiling ignites. When the basic kindling is burning nicely, open the firebox door and carefully lay on larger pieces of wood.

The type of wood you use will determine how long it takes your fire to get hot. Hardwoods (oak, fruitwood, etc.) are harder to get burning, but once lit burn hotter. Softwoods (pine, aspen) light more easily but burn up quickly. I like to use the end pieces from 2x4s or 2x6s (or other dimensional lumber), split with a hatchet, to start my fire. Then I add oak or juniper to keep it going. Occasionally I’ll throw in some more kindling if the fire is kind of slow.

You can begin cooking on the top of the stove fairly soon after starting the fire. High is on the left, medium is in the middle, and low is on the right, farthest from the firebox. Start on high and move your pan around to find the right spot. When the fire is burning well, adjust the draft to conserve wood and control the heat. Closed burns cooler, open burns hotter.

You can begin cooking on the top of the stove fairly soon after starting the fire. High is on the left, medium is in the middle, and low is on the right, farthest from the firebox. Start on high and move your pan around to find the right spot. When the fire is burning well, adjust the draft to conserve wood and control the heat. Closed burns cooler, open burns hotter.

By the way, cast iron cookwear can’t be beat on a cookstove. It heats up well, holds the heat, gives off trace amounts of iron, and will have your biceps looking wonderful (it’s fairly heavy). Keep your eyes open at swap meets and garage sales for used, already seasoned ware. Or you can buy new at hardware and other stores.

Keep an eye on the fire and add wood as needed. If you want to use the oven, let your fire get burning well, then close the damper on the back or side, allowing the heat to circulate around the oven. You may have a gauge on the oven door that tells you the inside temperature. I don’t completely trust mine, so I use an inexpensive oven thermometer. Be patient— the oven can take awhile to heat up. Just grab a copy of Backwoods Home Magazine to read while you wait. Place an old pan on the bottom of the oven and fill it with water before you bake. It will help keep your baked goods from burning. In the oven, the left side is hotter than the right side, so you may want to turn things around half way through the baking time. The temperature won’t stay constant as in an electric or gas oven, but if it’s close you shouldn’t have a problem. Once you have reached the temperature you want, use the draft below the firebox to control it.

You will have to clean the stove every so often. The frequency will depend on what type of wood you use and how often you cook. Using it full time and burning mostly pine, every one to two weeks is about right. If it seems like it takes forever to heat up the top of the stove, it’s probably time. Wear old clothes and find something to keep everyone busy for half an hour. Once you get started you don’t want to have to stop, if possible, because you will be having so much fun playing in the soot. When the stove is cold, remove the cooktop and brush the soot off the pieces. I do this over the stove so I only have to scoop the soot once. Push all the soot to the right hand side so it falls past the oven wall. There is a clean-out door someplace on the outside near the bottom of the oven door. Use a clean-out tool, which is a little rectangular piece of metal attached to a long handle, to pull the soot out. Put papers on the floor and get something to catch the soot. Close the doors and windows close by so your house won’t be peppered with killer soot balls. Scrape out as much soot as possible, using the clean-out tool. Shine a flashlight in the clean-out door to check the far corners for soot. By now at least your hands, if not much more of you, is completely black. This is always when friends will come to visit or your neighbor down the road will show up.

Once everything is soot-free, this being a relative term, reassemble the cooktop. You are now ready to go again. With practice, this cleaning will become easier each time you do it.

Wood cookstoves are very “user friendly.” I have found that with practice you can cook anything on a cookstove that you can on a regular stove. The only thing you need to remember is that food cooked this way is rarely “fast food,” but the trade-off for taste and the feeling of accomplishment is well worth it. You will come to know your stove in a way that is impossible with modern day appliances.

I would truly consider it a tragedy if I had to part company with mine, and friends like that are hard to find. If you should choose to travel this same road to self-reliance, I hope your experience will be as warm and enduring as mine.

Additional Research:

|