Grow Open-Pollinated Seeds for Self-Reliant Gardening

In the past I’ve grown hybrid vegetables, mostly the varieties that have been developed to produce early yields. Because of this, I was able to grow things like sweet corn in northern climates. However, from a practical point of view I am dead set against them if you intend to incorporate them into a “self-reliant” gardening plan. While these hybrids can taste good, I’ve found that most have been developed for commercial traits such as ease of shipping, holding saleable color and flavor for long periods, and for ensuring the simultaneous ripening of entire fields of a vegetable to facilitate mechanical harvesting.

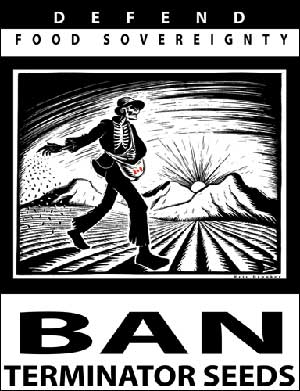

The one big negative is that hybrid seeds do not produce true reproductions of the mother plants. This makes buying new seed every year a necessary, expensive, and for someone who wants to become self-reliant, a dangerous practice. Monsanto has gone one step further in developing the “Terminator Gene” in field crops, which renders the seed produced in a farmer’s field sterile.

So, what happens if something unforeseen happens and we cannot afford to buy seed, or seeds just are not available when they are direly needed? The last year I grew hybrids —for market garden-ing—my seed bill ran over 150 dollars for three acres.

As a hard-core gardener, I believe in not only storing up at least a year’s supply of food in the pantry, but growing and saving open-pollinated seeds for future planting. This allows me to be in control of our garden.

Open-pollinated Veggies

There are several common complaints about open-pollinated vegetables. The first is that they don’t taste as good as hybrids. This is just plain wrong. For the last five years my family has been gathering and growing traditional, heritage varieties, largely from the Native American tribes of the U.S. and Mexico. With our family’s Indian roots, we initially did this out of curiosity, but we continued when we discovered some great tasting produce. Our ancestors had cultivated these vegetables for generations for exactly that reason. But, besides taste, most have had other benefits such as productivity, tenderness, winter storage, and hardiness.

There are several common complaints about open-pollinated vegetables. The first is that they don’t taste as good as hybrids. This is just plain wrong. For the last five years my family has been gathering and growing traditional, heritage varieties, largely from the Native American tribes of the U.S. and Mexico. With our family’s Indian roots, we initially did this out of curiosity, but we continued when we discovered some great tasting produce. Our ancestors had cultivated these vegetables for generations for exactly that reason. But, besides taste, most have had other benefits such as productivity, tenderness, winter storage, and hardiness.

Take my Hopi Pale Grey squash as an example. Five hills of squash produced two wheelbarrows heaped full of squash that are sweet and fruity tasting. They are much better than the plain-old hubbard or butternut squash. They are not stringy, but moist and tender. And they last in storage for better than a year.

By storage, I mean minimal care, under-the-bed storage. In fact, I have three right now under our clawfoot bathtub that are a year and four months old and will taste great when we get around to eating them.

On the otherhand, where some hybrids excel in sweetness and lasting ability in the fridge, they’ve lost such flavor traits as “corny” taste and tenderness.

A second complaint is that open-pollinated vegetables don’t grow big. This is often true. But while some hybrids, such as pumpkins and tomatoes, do get very large, our family would rather have such qualities as winter storage capabilities, intense flavor, and tenderness that are found in open pollinated varieties.

A third complaint is that they aren’t as uniform. And this is absolutely true. Open pollinated varieties are not uniform. But as a home gardener, I don’t necessarily want all my broccoli to mature at once and I don’t need all my squash to be exactly the same size and shape. In fact, one of the delights of growing Native American squash is that they are different, often one from it’s brother on the vine, lending beauty to the oft-drab squash patch.

Saving Seeds

Anyone can save their own garden seeds. Saving seeds takes very little effort and costs nothing after the first seeds are purchased. And you cannot only save your own seeds, you can pass them on to friends, relatives, and those in need.

The gift of food-bearing seeds is seldom taken lightly. Seed saving dramatically cuts gardening costs. Once you establish your own family seed bank, you will quickly notice that the cost of raising your family’s food has shrunk to a tiny amount.

Growing open-pollinated varieties also allows you a vast choice in old-time traditional vegetables. You won’t believe how many open-pollinated varieties are available from both growers of family heirlooms and seed houses, nationwide. While our family limits our choices to Native American crops, you can grow all sorts of ethnic vegetables that are open-pollinated. These include African, Italian, Amish, Russian, Greek, regional U.S., and many other vegetables. Every culture has its own.

Most open-pollinated varieties were developed over generations for hardiness in hostile climates, and growing through drought, wind storms, hail, and flooding. They had to adapt, and that adaptation produced extreme hardiness.

Basics for Seed Savers

Vegetables come in two types. The first is annuals such as corn, beans, and peas, which you plant each year and harvest seeds from in that same year. The other is biennials like cabbage, cauliflower, onions, and beets, which you plant one year, but the seeds are not harvested until the following year.

Vegetables come in two types. The first is annuals such as corn, beans, and peas, which you plant each year and harvest seeds from in that same year. The other is biennials like cabbage, cauliflower, onions, and beets, which you plant one year, but the seeds are not harvested until the following year.

Saving seeds from biennials takes a little more work since, in most climates, the plants to be saved for seed must be heavily mulched in the garden row or they must be stored in a root cellar over the winter so they can be replanted the following spring.

Gardeners must take care to keep their seed stock pure as some vegetables will cross-pollinate, creating a hybrid of uncertain productivity. The safest method to keep seed stock pure is to grow only one variety of each species, that is, one sweet corn, one pepper, one squash, etc. But few of us actually do this, opting for a few “cheater” strategies instead. For instance, I’ll plant a flour corn with late maturity dates alongside an early sweet corn. And, as they pollinate weeks apart, both remain pure.

Remember that some vegetables, such as corn, are wind-pollinated, and will cross with the neighbors’ corn or local field corn if their pollination dates are the same.

We grow several different peppers, both sweet and chile. I get by, avoiding cross-pollination, by making little “houses” over seed plants to prevent insect and wind cross-pollination. As peppers also self-pollinate, this practice gives us pure seed from many different varieties. The peppers destined for the table and pantry are not so protected, as we do not save seed from them and the cross-pollination does not affect them the first year.

For such crops as squash, of which we grow several kinds, I choose one squash of each of the four squash families. Generally, these will not cross-pollinate, giving us a great variety of squash each year.

You can check out which crops will cross by looking at their scientific name in a seed catalog. Crops with the same name will cross. Luckily, though, many are largely self-pollinating, and minimal spacing is required to keep seed stock pure. Beans and tomatoes are two common examples of such “easy” crops.

Seeds must be mature to save. Thus, save a few cucumbers from the pickle jar, leaving them to get huge and yellow; let several peppers stay on the vine until they get red; let summer squash mature until they look like garden submarines; allow a few stalks of sweet corn to get hard and dry.

Some seed may be saved from the vegetables you harvest to eat. These include winter squash, pumpkin, watermelon, muskmelon, dry beans, and sunflower seeds.

Mold and birds are the two biggest enemies of the seedsaver. All mature seeds must be kept from molding once they are harvested. And many birds, even your own chickens and turkeys, will open and gobble very mature produce to eat both the meat and seed. Some crops, such as sunflowers and amaranth, are also very tempting to your feathered friends, so when they are bearing fruitful seeds, it’s best to slip a pillow case over them, tying it loosely around the stem.

While most seeds are simple to harvest, requiring only stripping out of the mother fruit, some, such as tomato and cucumber, require a different approach, as it is too time consuming to get the seeds separated from the pulp. With these crops, pick ripe fruits, scoop out the seed-bearing pulp into a bowl or jar, add enough warm water to cover them, and place in a warm area such as the back of your counter for a couple of days. The pulp ferments and lets go of the seeds. After this happens, carefully rinse the fermented pulp-seed mass through a colander and soon only the seeds will be left. Spread these on a cookie sheet or pie plate and let them dry in a protected warm area.

When the seeds are very dry, place them in paper envelopes, then in an airtight glass jar. I usually skip the envelopes for large seeds such as corn, beans, peas, squash, and pumpkins, but I leave the jar top off a few days in a warm, dry place to complete the drying. The tiniest bit of moisture will cause mold in your seeds, ruining them.

Seed Storage Life

Generally, stored seeds will last for years. I’ve seen charts in seed catalogs and other literature, giving minimal storage dates for seeds, such as three years for sweet corn, a year for carrots, and so on. But I’ve got 10-yearold sweet corn seed that germinates at 90%, and I’ve planted beans that were over 700 years old and they sprouted and grew well. Heck, they’ve found wheat seeds in Egyptan tombs and planted it and it has sprouted.

So, you should keep your stored seed as fresh as you can, using the oldest seed and replacing it with new seed, but don’t worry if it gets a little old. Only onion seed is finicky, lasting for just a year or two before losing germination ability. Carrots, beets, and parsnips can be short-storers too, lasting about two to four years.

Run a Germination Test

When in doubt, run your own germination tests before planting in the garden. To conduct it, sprinkle a few seeds on a wash cloth, lay it in a pie plate, and soak lightly with warm water. Keep it warm and moist until germination occurs—from two days for some varieties up to three weeks for others. If only a few seeds germinate, they are too weak and no good. If half or more germinate, plant thickly and they’ll be okay. If most of them pop roots, your seed is in great shape.

If, as a self-reliant gardener, you get in the habit of raising your own seed, you will never be caught with your seed supply low. And once you start experimenting with all the neat open-pollinated varieties, you’ll truly be hooked and you’ll find that saving seeds from these old-time jewels is not only provident, but a lot of family fun. Our eight-year-old homeschooled son, David, can tell you a lot about cross-pollination, seed saving, and “having to” eat up a sloppy, delicious watermelon, just to get the seeds.

Additional Research:

|