Optimizing Your Homestead Farming & Gardening

Many of us have a garden and enjoy fresh vegetables during the summer and fall. Maybe we even have a few chickens for eggs and meat. But many of us may want to extend our homesteading to what I call “hard-core” homesteading. This is serious homesteading, aimed at being able to provide your family with nearly all of its basic needs. Luckily, most of us with a piece of out-of-the-way land can become nearly “store-bought-free,” raising much of what we need in nearly the same way as did our ancestors. There is a vast difference between this type of survival homesteading and stars-in-the-eyes, back-to-nature, recreational homesteading to relieve stress and provide enjoyment. The difference is not so much in how-to, but in discipline and learning.

The Survival Garden

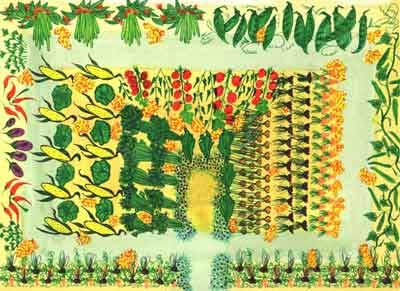

It has been said that one can raise enough food for a family of four in a 50- by 50-foot space. While such an area can provide a goodly amount of food, there is no way a family could survive, year-round, off such a small patch. In reality, all that this is is a “house garden” for providing fresh produce such as greens, broccoli, cabbage, peppers, herbs, etc.

When one needs a garden to put up food, not only for the winter but possibly for a year or two, we’re talking about at least an acre of intense cropping.

This includes a patch of wheat for grinding into cereal and flour; flour corn for hominy and corn meal; sweet corn for eating, canning, and dehydrating; and rows of dry beans as well as fresh beans (yellow wax, green, pole, etc.) for putting up. Here we stumble on the weak link in most folks’ gardens. They say “We only use a few pounds of corn meal or dry beans a year,” and they feel confident they can get by with just a few packages of such items, bought at the grocers.

This includes a patch of wheat for grinding into cereal and flour; flour corn for hominy and corn meal; sweet corn for eating, canning, and dehydrating; and rows of dry beans as well as fresh beans (yellow wax, green, pole, etc.) for putting up. Here we stumble on the weak link in most folks’ gardens. They say “We only use a few pounds of corn meal or dry beans a year,” and they feel confident they can get by with just a few packages of such items, bought at the grocers.

But having lived in a wild corner of Montana, well above the “grocery line” (because of road accessibility), I can tell you that you will use many more pounds of these staples when you cannot eat from the store shelves.

And if there are no store shelves to choose from, we will all need to take care of our own needs at home. Remember, it takes more than one year to get a garden into full production. You can’t just plow up a plot and expect to survive off of it, especially if you lack experience.

You can’t grow everything, everywhere. Look at your local production capabilities. Here in New Mexico I can grow anything. In the high country of Montana, nearly everything was a challenge even though I’ve gardened all my life. But we could survive from my Montana garden with potatoes, wheat, and beans along with a number of cold-loving crops we grew. What you need to do is put your energy into growing what will make a crop in your location.

But don’t be afraid to experiment. Everywhere I’ve gardened I’ve grown crops that locals said “wouldn’t grow.”

To better use space, consider interplanting as much as possible. Grow cornfield beans among the flour corn, radishes in the same row as carrots, peppers between rows of tomatoes (which act as windbreaks), pumpkins and squash next to a corn field where they can run into the corn after cultivation has stopped. (Don’t do this with sweet corn or you will have a devil of a time picking the corn stumbling among rampant squash vines.) Inter-planting will do much to save garden space, a large consideration in survival gardening, especially when you must cultivate and till by hand.

Crops For A Survival Garden

Everyone who gardens grows some things just because they enjoy the taste. This is great, and we all do it. But in hard-core homesteading, we must consider our basic needs, as well.

We need to grow enough grain and corn for ourselves and livestock. This can be done by hand, in a relatively small plot, provided that our poultry and livestock needs are small. If you need more grain, say for cattle or horses, consider small scale farming with horses. This is a sustainable way of living as horses are easy to work, versatile, and provide manure for the fields. They also require no fuel to run. One team of moderate-sized horses can do as much work as a small tractor and cost little to maintain.

As little as an acre of ground can supply modest grain needs for a fami-ly homestead. Include a bit of rye, oats, and barley for variation. (There is a naked-seeded oat that is great for homesteaders, as at home one has a difficult task in hulling oats for oatmeal.)

Besides small grains, include your rows of flour corn for corn meal and hominy, being sure to include enough for livestock feeding.

Most folks have to double or even triple the amount of usual garden produce to allow for putting up as much each year as possible. Be sure to allow for lots of tomatoes for tomato sauces, and enough root crops, such as turnips, potatoes and carrots. (You’ll eat a lot more “homegrown” when you can’t run to the store for “quick” meals.)

With all survival garden vegetables, a family should buy only open pollinated varieties. This will enable folks to save seeds from year to year, which is not recommended with hybrids. Hybrid seed, while usually fertile, can not be depended upon to reproduce truly. And, contrary to popular belief, most of those old open pollinated varieties are good tasting and hardy.

Perennials For The Survival Garden

Along with the vegetables, a hardcore homesteader should establish a good variety of perennial edibles. These include asparagus, Jerusalem artichokes, horseradish, garlic, perennial onions, and herbs for both culinary and medicinal use. Remember to encourage native perennial edibles which do well in your area. These may include prickly pear cactus (the fruits and pads are eaten as a vegetable), wild rice, wild greens, cattails, mushrooms, etc. In a survival situation, one truly appreciates variety in the diet.

The perennials have the advantage of having to be planted only once and usually expand on their own with little human help. And, like the annuals, which must be planted each year, a family can gather and put up many jars full of winter eating. I can wild and domestic asparagus, wild mushrooms, wild greens, cactus pads (known as nopalitos in the southwest), and dry many other wild and domestic perennials.

Small Fruits Are Nearly Essential

Nearly everyone has room to plant a good selection of small fruits. These include strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, rhubarb, blueberries, and so forth. Luckily, once a patch of each has been established, one can readily take divisions or replant sprouts to greatly increase their food-producing capabilities.

As with the vegetable garden, one should grow as great a variety of small fruits as possible, and enough of each to put up significant jam, preserves, and canned and dried fruit. In hard times, a good loaf of hot whole wheat bread spread thickly with homemade strawberry jam, or a steaming blueberry pie, makes the term “survival” a joke. We call it living good. You quickly discover that small fruits are a wonderful treat that can be easily turned into strawberry shortcake, blueberry pancakes, rhubarb tarts, blackberry cobbler, etc. In hard times, you don’t eat many candy bars; instead you substitute healthier fruit snacks and desserts.

Even picky eaters greatly enjoy dried fruits and fruit leathers which are easy to make at home.

Every Homestead Should Include A Small Orchard

Even the smallest homestead has room for fruit trees. With the variety of tree sizes and shapes, you can choose full-sized trees which are tremendous producers, but take room and several years to begin bearing fruit. Semi-dwarf trees, which usually require only a 10- by 10-foot spacing, produce full sized fruit in moderate amounts and only take a couple of years to bear. Dwarf and “pole” trees, which produce full sized fruit in small amounts, can be raised on a patio in a portable tub.

A hard-core homesteader can get by with two each of several varieties to provide variety and cross-pollination. I’d suggest apple, pear, pie and sweet cherry, apricot, and plum for most gardeners. Of course, if you can grow citrus in your zone, go for it. We live in zone 5 and have two Brown Turkey Figs in a protected corner of our east flower bed—protected by the house from the killer winter north winds.

Now a lot of folks say they’d need acres and acres to reach this level of self-reliance in the food department. Not so. My grandmother did it on two city lots in Detroit. Instead of normal landscaping, nearly everything she grew produced edible fruit: peach, grapes, brambles, quince, asparagus, apple, crab apple, strawberry, etc.) Having gone through the Depression as a widow with two young boys to raise, Grandma knew how to fend off hard times.

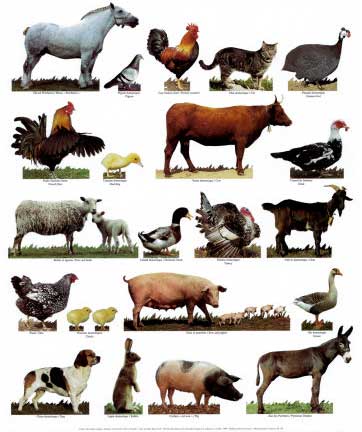

But What About Meat?

Like produce and fruit, a family can grow all of their meat requirements, right at home. Now few people actually like to kill to eat, but when it comes down to eating or not eating meat, most of us can find a way around our revulsions. After all, someone had to kill that steer that went into your Big Mac. It gets ridiculous when visitors won’t eat a home-butchered beef roast but will buy a tainted, chemical-laden piece of plastic-wrapped roast at the supermarket and eat it with abandon.

Folks on a very small acreage will usually have to limit their meat production to poultry, rabbits, and perhaps a little goat meat. A small flock of chickens for egg and meat production, with a couple of hutches of rabbits and the castrated male offspring of the family dairy goats will do much to help out at the dinner table. Of course, a family with these reduced production capabilities will not eat meat every day, but it will be able to enjoy regular meals with meat as a feature.

The benefit of having only a small poultry flock, a few hutches of rabbits, and very few goats is that the feed requirements and labor requirements are also minimal. In such cases, a family can easily hand-raise and harvest all feeds necessary to maintain their meat and egg supply.

Small-holders can help supplement their meat needs by hunting and fishing. But remember, if times are hard nationwide, subsistence hunting will become very difficult in most areas, as it did during homestead days and during the Depression. The game quickly disappears with over-hunting. Fishing holds up much better, so it benefits a family if they hone fishing skills before they are truly needed. (Besides, it’s enjoyable family “work,” as well.) For lucky backwoods dwellers who live near the seacoast or a salmon stream, fishing can well be the major source of family meat. Folks with more acreage are in better shape to truly be meat self-reliant.

Using horsepower to till moderate amounts of land, a family can raise enough small grain, field corn, and forage (hay and pasture) to maintain not only the horses but a couple of dairy cows or several dairy goats. Let me stop right here and address you folks who are saying, “Goats! No way am I going to raise those stinking tin can eaters!”. Goats do not eat tin cans, nor do they run around butting people, any more than do cattle. Goats are exceptionally clean, picky eaters, refusing to take a bite of the apple you just took a bite out of, and they’ll dehydrate before they will drink from a bucket containing even one berry of manure.

Only bucks in rut have any odor. While in rut they will spray their neck, belly, and chin with urine as an attractant to does in heat. So do elk and deer. The normal scent glands on a buck’s head, which produce scent during rut, can be removed by surgery when the buck is an adult or during de-budding, leaving a scent-free male totally capable of breeding. Does never have an objectionable odor, and with neat droppings the pen is quite clean and odor-free with even minimal daily maintenance. We’ve had both dairy goats and cattle, and we know the benefits and drawbacks of each. Both produce milk which is equally good-tasting. A goat often produces multiple offspring while a cow produces one calf a year.

Cattle are easier to fence in, but goats will do great in a pasture grown over to willows and brush as they are by nature browsers like deer. And, like deer, they can hop a four-foot field fence to enter your young orchard and strip the tender trees of their bark and twigs. Cows produce beef; goats produce chevron. Both are good, but different.

Chevron comes in carcass weights from between 20 and 100 pounds of dressed weight, depending on age. They are easier to cut up and handle, cut their small carcass lasts a much shorter period of time than a 600-pound Angus carcass.

Remember that worldwide there are thousands more goats used for meat and dairy production than there are cattle. There are reasons, and economy is at the top followed by the quickness of meat consumption in areas without refrigeration. A 600-pound cattle carcass is likely to spoil before it’s completely consumed.

Pigs are another cog in the serious homesteader’s wheel of self-reliance. Not only can a few pigs easily be raised for butchering—being fed from home-produced feed, kitchen and dairy waste (skim milk is an excellent food), along with weeds, pasture, and hog-foraged feed—but they provide excellent meat with a carcass that is quite easily handled by the family. The bonus of hogs is that they produce lard, the only homegrown cooking fat easily obtainable.

Yes, I know about high cholesterol, but let me tell you that when you are working hard everyday to put food and other necessities on the table, your cholesterol will balance easier than your finances.

Homegrown Dairy Products

Okay, so far you have a good vegetable plot, small fruits, small grains, and an orchard and meat/egg supply started. It’s time to think about dairy products, particularly milk and cheese. After that stored dry milk is gone, your family will want something to replace it. And what is more natural than learning to run a tiny kitchen dairy and cheese plant? All dairy products are quite easy to produce at home, and as with almost everything else, it’s much better when homemade.

I’ve made cottage cheese, cream cheese, mozzarella, colby, cheddar cheese, sour cream, cheese spreads, balls, logs and sandwich loaves, ice cream, ice milk, sherbet, and more regularly at home, both from cow and goat milk. Butter and whipped cream are easier to do from cow milk, as the cream quickly separates out, floating to the top. Goat milk is naturally homogenized and it takes more “doing” to access the cream. Both animals’ milk produces good-tasting dairy products.

A good milking doe goat will produce about 3 quarts each milking, on average, where an average milk cow will produce much more—about three gallons. So your choice will depend on your facilities, labor and needs.

Remember that all “extra” milk can be used to produce dairy products such as butter (which can also be used as a cooking fat) and cheese; dairy by-products can be fed to chickens and hogs. Extra milk can be used to bottle feed young calves or kid goats. On a survival homestead, there is no waste!

When planning on establishing a home kitchen dairy, be sure to stock up on such things as rennet tablets, which make forming cheese curd much easier and more reliable, cheese cultures (as you need for some “fancier” cheeses), cheese cloth and a cheese press or the materials to make one. These materials can be as simple as a #10 can or a 4-inch piece of PVC pipe and wood.

Okay, now we have your family ready with a vegetable garden, small fruits, grains, orchard, meat/eggs, and dairy production. Pretty nifty, right? You bet. For now you can also make soap from used cooking fats, which you can save in a can after each use.

Soap making is easy and glitch free, requiring only strained, clean used fat and lye (which can be produced by seeping water down through wood ashes). This soap is great and can be used to wash clothes, babies, and hair.

Add a hive or two of bees, and your sugar requirements are easily met. Then too, the bees will pollinate your entire garden, grain patch and orchard, ensuring bountiful harvests. Bees are easily established and easy to work with. I’ve only been stung twice working with domestic bees, and probably a few dozen times by “wild” bees.

Survival homesteading is addicting. Once you get started, your mind works constantly at ways you can do more to be less reliant on the system. Now I say “can do” as few homesteaders actually practice every bit of their knowledge. I can raise and shear sheep, spinning wool into yarn to make clothes. And I can tan hides from which to fashion clothes and footwear. But I choose to use my time in other ways, which are more productive to the family at present. But the knowledge is there, should our needs change.

Survival homesteading is rewarding, financially and spiritually, as a basic instinct in human beings is to provide for their own and their family’s needs. Never become overwhelmed by feeling that you must do everything at once. It is better to proceed in steady forward steps, rather than to run forward, fall and lose heart. One vital tip: start small and work your way up as your ability and knowledge increases. Your survival homestead depends on it.

Additional Research:

|